In 1849, Andrew Carnegie—then a poor teenage immigrant from a one-room home in Dumfermline, Scotland—worked as a messenger at the Pittsburgh branch of the Ohio Telegraph Company. His salary: two dollars and fifty cents per week.

As David Nasaw’s biography Andrew Carnegie explains, that wasn’t enough even for a fourteen-year-old Carnegie.

Besides the low pay and his need to help support his family, there were a few obstacles in front of his career prospects.

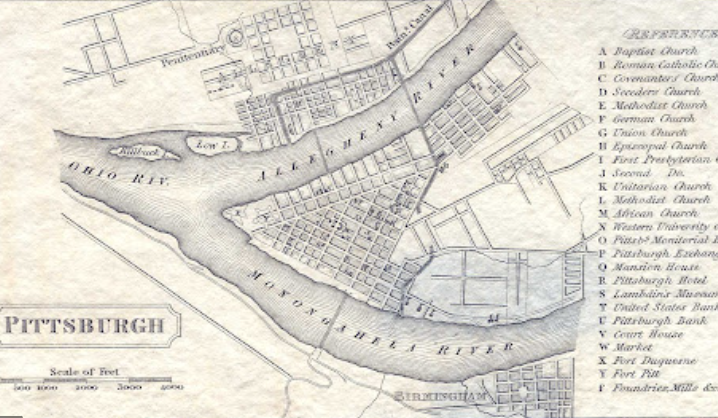

The most immediate: Pittsburgh was a strange city—not a straightforward grid like Manhattan. Delivering messages would be a nightmare for someone who didn’t know the lay of the land.

So Carnegie memorized Pittsburgh’s street map cold.

Once he knew the map, he learned the names and faces of Pittsburgh’s business people. In the days before widespread photography (let alone Google Images and LinkedIn), he could identify business executives on the street to present them a message delivery “on the spot.”

He even taught himself to take messages by ear rather than waiting to copy the printed slips.

When Carnegie transitioned from telegraph operations to the railroad business, he brought the same principles:

He ingratiated himself with supervisors, learned as much about the industry as possible, and did more than was expected of him.

For six and a half years in Carnegie’s 20’s, he worked as the assistant to railroad superintendent Tom Scott:

He tied himself to Tom Scott’s coattails and never let go. Whatever Scott wanted, Andy took care of it.

…

Carnegie watched, listened, learned. Nothing was lost on the young man. With an exceptional memory and a head for figures, he made the most of his apprenticeship and was acting more as [Tom] Scott’s deputy than his assistant.

When opportunity struck, Carnegie moved heaven and earth to capitalize. Carnegie’s first dividend-bearing investment required him to take out two loans:

Because Andy didn’t have the cash to buy the stock himself, [Tom] Scott loaned him the $500 he needed. When, six months later, Scott’s note came due, Andy borrowed the money to pay back his boss, and then arranged, through his mother, to mortgage off their newly acquired property in Allegheny City to cover the costs of the second loan. In the end, with the help of his mother, he acquired the stock and the guaranteed ten-dollar monthly dividend check that came with it.

So what am I getting at?

“Do your duty and a little more and the future will take care of itself.”

Andrew Carnegie

Granted: Carnegie’s story is complex. Try to put a finger on it and it will elude you. He made the most of his relationships to conduct insider trading, which was legal at the time. He also gave away the equivalence of hundreds of billions of dollars. He squashed worker strikes with shady practices. He also blazed the trail for the modern uberphilanthropist.

But his story is certainly not accidental.

His habit of doing more than was expected of him didn’t only make his rise possible. It was inevitable.

This is hard for most people, myself included. But every so often I like to open David Nasaw’s book and remind myself how hard Andrew Carnegie worked when he was a poor child from across the sea with no prospects, no connections, no promises for the future, and had to pay up his entire his paltry salary to the support of his family.

Extra hours studying maps. Learning faces. Building new skills. His company incentivized none of this. There was no promise of future advancement. There was not anything remotely resembling a corporate ladder that led directly from “telegraph operator” to “business tycoon.”

Despite it all, he didn’t despair. He was looking upwards. He gave his company more work than they paid for.

In the 9-to-5 culture, there’s often an underpinning collective moan of “work stinks and we should all be sardonic about our reluctance to even be here.”

Doing more work than others means you’re trying to “make other people look bad.”

Or it means you’re “sucking up.”

Humbug.

I used to keep Carnegie’s quote pinned on my Twitter profile to remind myself that there’s another way to view hard work: as an investment in yourself.

Yes, sometimes it’s thankless.

No, sometimes you won’t get paid back for giving a job 105%.

Yes, opportunities come staggered and irregular rather than in an IV-drip supply.

But as a habit, it’s the right way to go. We should all try to incorporate Carnegie’s lessons in our daily lives:

Excel Where You Are, But Change When Opportunity Strikes

In the telegraph office, the most advancement Carnegie could hope for was moving from messenger to operator—which, thanks to his efforts, didn’t prove to be a problem.

But that’s where the career ladder ended.

When Tom Scott needed a private operator to handle the new telegraph poles going up along his Pittsburgh-Allegheny railroads, he offered the position to local telegraph wizard Andrew Carnegie.

By this time, Carnegie could have accepted a pay increase to stay put. Instead, he chose the lateral move. The opportunities in the railroad business provided, as he wrote, “better prospects for the future.”

This focus on the long-term may make you feel stagnant in the present, but it’s often necessary. Like digging out a plant just to put it in better soil, it won’t produce rewards immediately, but it will eventually result in a taller plant. (Can you tell I’m not a gardener?)

Download All the Knowledge You can

One of the areas I struggle with is viewing myself as a “quick learner.” It’s not an advantage. I figure with a little light research, a few paragraphs read, and I’m there. Then I find out later that I should have used a better source, read a little further, or taken just another few moments of my time to get it 100% right.

Maybe I am a quick learner, but it’s better to be a thorough learner.

What is your Pittsburgh road map? Who are the people you have to know in your industry? What skill can you learn in your downtime to make you faster, better, more reliable in your line of work?

Until we develop the Matrix-style “I know Kung Fu” technology to instantly download all relevant information we need, we’re stuck with reading, listening, and learning.

Like most work, this labor isn’t always easy. It’s an upfront investment. But it’s one that’s almost guaranteed to pay dividends.

To Get the Most From Your Investment, Give People a Better Return on Theirs

Let’s go back to the “work stinks” people for a moment.

Work stinks? Really?

It takes a lot to employ a person full-time in 2021. Tens of thousands–if not hundreds of thousands—in salary. Benefits. Time. Energy. Management. Vacation time. An annual raise. Employee training. Compliance training.

For many fortunate people, the irony of complaining about gainful employment while enjoying a climate-controlled break room is rich indeed.

I do my best to take any investment in my labor seriously. When people spend hard-earned money on my services, I want them to feel like not only was the money well-spent, but I also made their entire life a little easier.

I’m not 100% successful. Like anyone else, I’m at the mercy of flesh-and-blood limits.

But for any work to be sustainable, the person on the other end of the check has to get something out of their investment. Why spend $50,000 a year on you if your labor is only worth $45,000? Or $20,000, for that matter?

These imbalances have a way of catching up to people. You can either let that imbalance work in your favor, or work against you.

It’s your choice.

That’s why it’s important to make sure that you give people a return on their investment in you.

When that happens, they’re more inclined to return to you next time. They’re more inclined to recommend you to someone else. Eventually, you’ll find equilibrium tipping in your favor.

Even if you start with $2.50 a week.