Resisting Something is a Sure Way to Get More Of It

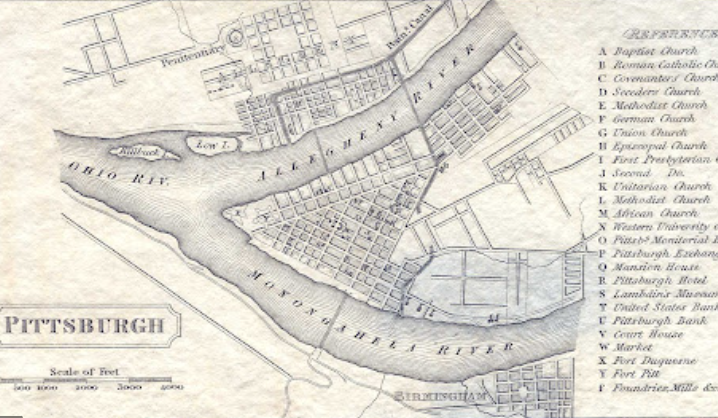

The scene: June 1791. The height of the French Revolution.

By then, Louis XVI and his wife Marie-Antoinette were already exiles from Versailles. Two years earlier, the mob had marched on the palace and forced the royal family to relocate to Paris.

Their situation was perilous: the mob kept them under lock and key at the palace of Tuileries. Languishing in Paris, the royal family was dangerously close to the people who hated them the most.

But they weren’t idle. Marie-Antoinette’s court favorite, the Swedish Count Axel von Fersen, helped hatch a plan. The royal family would disguise themselves and attempt a daring escape east to Montmedy.

To make the journey quickly, they would have to split up the royal family into multiple, smaller carriages. But Marie-Antoinette insisted her family travel together. They replaced the plan for two carriages with a bigger, heavier, more obvious six-person monstrosity.

For his part, Louis XVI figured that if there was any trouble, the royal family’s popularity with the peasants would win out.

It did not.

The attempted flight to Montmedy became the ill-fated Flight to Varennes after a postmaster saw Louis XVI and double-checked the currency he had on him. (One can almost imagine the postmaster pointing and saying, “Hey, aren’t you…?”)

It didn’t help that the large, obvious, opulent carriage drew suspicious eyes.

The royal family was ultimately arrested. But even more alarming,: the attempted escape was like throwing a rock at a beehive. Seeing the king and queen try to escape in such an embarrassing, out-of-touch manner only stirred up more anti-royalist resentment.

Says Wikipedia:

From this point forward, the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic became an ever-increasing possibility. The credibility of the king as a constitutional monarch had been seriously undermined by the escape attempt.

Though Louis XVI could have acquiesced to the political revolution plainly taking place around him, he refused. Instead, he…

…rejected the advice of the moderate constitutionalists, led by Antoine Barnave, to fully implement the Constitution of 1791, which he had sworn to maintain. He instead secretly committed himself to a policy of covert counter-revolution.

Pressure also built up outside France’s borders. The War of the First Coalition broke out in 1792, and a Prussian Duke even threatened to destroy Paris if the royal family was harmed.

This did not calm the radicals. They were radicals, after all.

Those radicals eventually responded by storming the Parisian palace. Louis XVI was arrested, imprisoned, and ultimately beheaded.

Story #2: How to Keep a Mutiny at Bay, by Alexander the Great

The scene: Opis, 324 B.C. Modern-day central Iraq.

Alexander the Great had just conquered the known world with his army of Macedonian veterans. Though the army was fat with plunder and victory, an underlying tension developed on Alexander’s long campaign.

Alexander had initially promised to punish the Persians for their incursions into the Greek Peninsula. But now, with King Darius III long gone and the Achaemenid Empire only a memory, the tenor of the campaign changed.

Alexander took Persian wives. Adopted Persian customs. Kept going east—into mountains, jungles, and inhospitable terrain. Though the army had gained fame, riches, and glory during the Persian campaign, they were homesick.

Finally, one day in India, the army finally cracked. They mutinied and demanded they go home. Alexander decided to give in to his army and started the long journey back to Europe.

But it wasn’t enough. A trek through hostile terrain on the return trip through southern Persia claimed countless lives. Alexander initially sent some Macedonian veterans home with money—ostensibly to thank them—but his army misinterpreted this as dismissing his Macedonian influence and going fully over to the Persian side. They mutinied again.

Though Alxender’s response was harsh (he arrested some of the mutineers), he also gave a remarkable speech that did something you might not expect from Alexander.

He essentially said: go ahead. Leave.

Rather than being executed by his people like Louis XVI, this speech helped lead to an emotional reconciliation.

Story #3: Benjamin Franklin and the Gulf Stream

The scene: England. 1768. Benjamin Franklin, traveling abroad, overheard a complaint at the Colonial Board of Customs. British packet ships sailing west to New York took several weeks longer than the average merchant ships took to reach England from Rhode Island.

Franklin reportedly asked his cousin (and whaling captain) Timothy Folger about the issue. Folger informed him that among merchant ships, it was common knowledge that you had to sail against a hard mid-Atlantic current coming up from the south.

The current was the Gulf Stream. And according to Folger, whalers knew that the best way to deal with it wasn’t to sail into it. It was to cross it as soon as possible, getting south toward friendlier waters.

Meanwhile, the British packet ships kept going straight into it—and many couldn’t figure out why it lengthened their journey by weeks.

Resisting Something is the Surest Way to Get More Of It

I use three examples from history because there’s a principle at work here. And that principle seems to bear out in all sorts of different places. Sailing. Relationships. Military leadership. Anxiety. Psychology. Ruling the French House of Bourbon.

Resisting something is the surest way to get more of it.

When we resist bad things, we tend to make them worse. While we imagine ourselves as being proactive and dealing with the problem, we may actually be exacerbating it. We intensify its energy; we feed coals into the furnace.

It’s ancient wisdom that reverberates all through the world’s major religions. Jesus said, “Offer no resistance to one who is evil. When someone strikes you on [your] right cheek, turn the other one to him as well.”

Most people interpret this as fighting advice. I think it’s life advice.

Once you’ve accepted this advice, you start to see its benefits everywhere.

- Dealing with authority. Ever see those YouTube videos of people pulled over for routine traffic stops essentially berating officers and yelling about their rights? It’s possible to be technically right while also doing the wrong thing. Why would you antagonize someone who has the power to write you a ticket? Also, resisting arrest: always a bad idea. Check out these people who turned a request to leave a park into them getting arrested.

- Political protest. Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of nonviolent protest had devastating power in highlighting the virtues of their cause. Simply going in to sit at a lunch counter chair and being arrested for it helped showcase the ridiculousness of Jim Crow laws. Had MLK fought with police, he would have only given ammunition to his critics.

- Avoiding fights. Someone on Twitter once sent a UFC fighter hate mail on Twitter. The UFC fighter actually responded: “Does it make you feel good saying that? Now would you say that to my face man to man?” Rather than dig in, the Twitter user responded with: “Nope you’d kick my ass that’s why I said it on twitter.” Fair enough, the UFC fighter responded. And both went their separate ways.

- Making friends. Writes Dale Carnegie: “I know and you know people who blunder through life trying to wigwag other people into becoming interested in them. Of course, it doesn’t work. People are not interested in you. They are not interested in me. They are interested in themselves…” Carnegie goes on to write that the best way to make friends is to swim with the current of human nature: become interested in other people.

- Panic attacks. Dr. Harry Barry, an expert on panic, often recommends not fighting the cause of panic: the amygdala inaccurately sending “danger” signals to your body. He recommends a different approach: imagining that your feet are plastered to the ground and you can’t move. If you don’t resist the panic attack, he says, within about 10 minutes your amygdala figures out there’s no threat and you return to normal.

- Leadership. We saw Alexander the Great’s example. Yet you hopefully don’t deal with mutinies after leading successful Persia-conquering campaigns. What’s a modern-day example? When you have to correct someone: do you argue with them about why they are responsible for messing it up and argh why are they always making life hard for you? You’re resisting. Simply focus on the error instead. Don’t say, “You messed up and didn’t send me the attachment.” Say, “The attachment didn’t come through.”

- Playing dead. Apparently it works on bison.

- Falling asleep. Matthew Walker, author of Why We Sleep, recommends not fighting it if you can’t fall asleep, but rather to get out of bed and do something else for a while, then re-trying later. In fact, it’s a bad idea to continue to keep trying to fight for sleep. You need to associate your bed with total relaxation and weariness, not with the frustrated feeling of insomnia. Associate the couch with being awake; let your bed be for sleeping.

- Settling arguments. This brilliant Reddit comment says, “Instead of saying I know, say You’re right.”

You get the point.

If something is too hard—like sailing across the Atlantic Ocean—it may not be because you’re destined to fail and you should immediately give up.

It may be because you’re going against the current.

Rather than giving up, try a different tactic: non-resistance. Adjust strategies rather than digging in. If you’re going against the tide, simply sail south until you’re free of it, then turn west again.

And stick to small carriages.

Like the stuff you just read? Want that stuff on your blog? Let’s talk stuff. Hire me to write stuff like this for you.