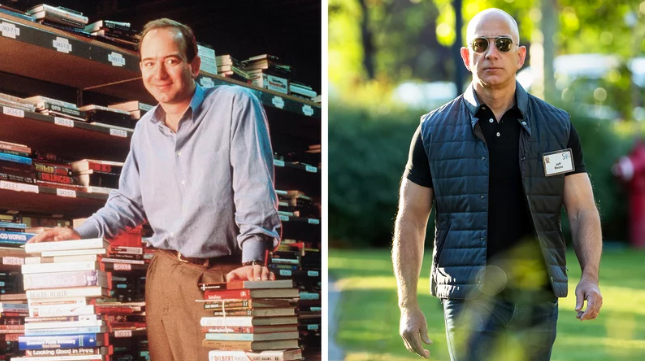

In 1994, Jeff Bezos was a young vice president at D.E. Shaw & Co., a Wall Street investment firm. The firm had a reputation for innovation and challenging the status quo. So maybe it’s no surprise that several times a week, Bezos would meet with the founder, David Shaw, and brainstorm ideas for an emerging technology with a lot of promise: the Internet.

Bezos had noticed the World Wide Web’s incredible 200,000% growth. Between January 1993 and January 1994, the number of transmitted bytes on the Web had increased by a factor of 2,057.

“Things just don’t grow that fast,” Brad Stone quotes Bezos in his book The Everything Store. “It’s highly unusual, and that started me thinking, What kind of business plan might make sense in the context of that growth?”

Bezos’s brainstorms with Shaw yielded a few ideas that would all eventually prove practical online:

- Free, ad-supported email

- Trading stocks online

- An “everything store,” where one intermediary could connect manufacturers with customers, with an open-ended customer review system

Bezos concluded, writes Stone, that a true everything store would be impractical, at least in the beginning.

It’s worth repeating:

At least in the beginning.

The Leverage Ladder: Starting Where You Are to Build Massive Leverage, Eventually

One of the most important concepts in business is leverage.

This isn’t referring to negotiating power or a thumbscrew you can twist on another person. I mean it in the most mechanical way possible: with a lever, a human can use an 18-foot lever to lift 800 pounds.

Writes Eric Jorgenson:

Can you lift 800 pounds? You could with an 18-foot lever.

Can you earn $50,000/year without working even 1 hour? You could with $1,000,000. (leverage from capital)

Can you get 100,000 people to read your tweet? You could with 100 retweets. (leverage from an audience)

Image Source: Eric Jorgensen

One day, as I was looking up how car engines work because I am a nerd with too much time on my hands, I discovered internal combustion was simpler than I thought. It’s a system of tiny explosions to kick-start a series of levers:

- Take the concept of a lever (small input, major output)

- Add more levers, and turn it into a wheel, and you’ve got a gear

- Add enough gears, and eventually, small movements (pistons moving, a foot hitting the accelerator) become a one-ton car moving at 60 miles per hour

With the right lever, you can lift 800 pounds. With the right leverage ladder, also called an engine, you can move a two-tone machine with a spark plug.

The problem is, most of us look around and don’t see powerful levers. We only see the ones we have available to us. I can’t reach a million people with one tweet, for example. A celebrity can.

Even Jeff Bezos, who was in the right place (Wall Street) at the right time (dawn of the Internet), couldn’t wave a magic wand and bring the Everything Store to life overnight.

But he could press the first lever he saw.

For Bezos, that lever was selling books.

Building the Everything Store…But Not Yet

According to Stone, Bezos listed twenty possible product categories for this “Everything Store.” Software. Office supplies. Apparel. Music. But one category stood out: books were ripe for the selling.

[Books] were pure commodities: a copy of a book in one store was identical to the same book carried in another, so buyers always knew what they were getting…and, most important, there were three million books in print worldwide, far more than a Barnes & Noble or a Borders superstore could ever stock.

If he couldn’t build a true everything store right away, he could capture its essence—unlimited selection—it at least one important product category.

Soon thereafter, Bezos and a colleague ordered a book online—Isaac Asimov’s Cyberdreams. The book arrived two weeks later, badly tattered.

If Bezos could figure out how to sell books better, he had something. No one had figured out the Internet delivery of books yet.

He’d found his first lever.

Bezos, using his “regret minimization framework” and reasoning that when he was old, he wouldn’t regret taking the biggest chance of his life, left D.E. Shaw & Co.

According to Bezos’ father Mike, his parents’ first reaction to getting this call was: what do you mean, you’re going to sell books on the Internet? They suggested he work on his venture in his off-hours.

But it was too late. The young Bezos’ enthusiasm had already taken root. He quit, moved to Seattle, and started brainstorming business names. (An early one they discarded: Relentless.com, which sounded too sinister. Bezos still owns the URL; try it out and see what happens.)

There wasn’t much money to speak of. Bezos gave the company $10,000 in cash. Another early employee, Shel Kaphan, bought $5,000 in stock. A $100,000 investment the next year from Bezos’ parents. A few loans. And even after that, this what Amazon’s first website looked like:

It was the Spring of 1995 when the first Amazon.com links went out to friends, family, and former colleagues. These constituted the available “levers” they had at the time.

Kephan’s former coworker, John Wainwright, made the first purchase: Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies. Amazon had no storage, so they’d order the books themselves, with Bezos & Co. sometimes doing the packing and driving to the post office when the company got behind.

Amazon was an instant success. Book money became investor money became reinvestment money. Amazon was public by 1997. Selling music and videos by 1998. Selling games, electronics, and home improvement products by 1999. Amazon Web Services by 2002. Enough infrastructure for Fulfillment by Amazon by 2006. Purchasing Whole Foods in 2017.

“Today,” writes Stone, “a building on Amazon’s Seattle’s campus is named Wainright.”

Start Pulling Levers Where You Are

We can only pull the levers available to us. Privilege, wealth, opportunity, geography, childhood experiences, personal networks, and knowledge all play into which levers those are.

But if you’re lucky, you’ll notice a few levers. They do exist. You just have to know how to find them, even if they don’t create Amazon-like success right away.

According to Naval Ravikant, there are four types of levers:

- Capital (money, investments earning for you while you sleep)

- Labor (another form of capital; hiring someone to do something for you)

- Code (creating an app once and selling it a million times)

- Media (a million followers on Twitter, writing a book once and selling it for years)

These follow a common pattern. Take the abundant resources you already have, such as capital or a rare skill, and trade them for something you need but which doesn’t require any extra work on your end.

The best levers are those you only have to pull once, yet keep creating results.

In writing and ghostwriting, I’m often someone else’s lever. They use capital to hire my labor, and I create media for them. If all goes to plan, their actual involvement is minimal.

Eric Jorgensen lists some of his subscribers’ 50 “first” levers you can explore. Some of them are pretty inconsequential lifestyle upgrades, like getting free weather reports or signing up for HelloFresh to minimize meal prep time.

The key to the leverage ladder is that you use your levers not for these tiny wins, but with your eye on building levers with increasing strength.

And that’s the challenge. Bezos recognized a rare opportunity—digital bookselling—which made Amazon a near-overnight success. That success included reinvesting and compounding its returns until Amazon genuinely became an “Everything Store.”

Signing up for HelloFresh won’t get you there.

But that’s okay. If signing up for HelloFresh saves you an hour a week that you spend on improving your business, at least that moves the needle. You now have an hour of time to pull another lever.

And on and on the ladder goes.

The challenge for most people is lifestyle creep. They sign up for HelloFresh and waste the extra time. But if you can sustain an interest in your Personal Leverage Ladder™, those returns can compound over time.

Average returns sustained for an above-average period of time leads to extraordinary returns.

The trick is to be aware of levers and their power, then to sustain an interest in them. To consistently build them for ourselves with an eye on creating outsize impact with consistency. To spot levers when they look like losses. Early in Amazon’s life, the company was losing money—$52,000 in 1994. Bezos told both his parents and investors that he put their chance at failing at 70%.

Yet a well-placed investment in Amazon stock in the mid-90s would have eventually created life-changing wealth.

The key with the leverage ladder is not to see things as they are, but as they can be a few years down the line. Amazon’s first website looked atrocious. Yet it had the potential to personalize a shopping experience for new users. Amazon’s first logistics often had Bezos and his then-wife (and Amazon’s bookkeeper) driving to the UPS store. Yet the demand for books funded new hires like Laurel Canan, a carpenter who built Amazon its first packing tables. “If you’re successful,” one investor told Bezos, “you’re going to need a warehouse the size of a Library of Congress.”

Well, yeah. Says Stone:

Though they could not have known it, investors were looking at the opportunity of a lifetime.

One key: Bezos’ vision. Books—the orders of which were threatening to bury Amazon in a backlog—were just the first lever in the engine that would become the Everything Store.

What Levers Can Writers Pull?

Media: Blog Posts, Social Reach, Newsletters

For writers, the most obvious lever is media. Hopefully, we’ve developed the skill of creating things people want to read.

Take my summary of James Clear’s Atomic Habits. I only had to create that once, yet it lands hundreds of people on my website every month. That traffic takes place with zero ongoing effort on my part. That’s a tiny media lever, pulled once.

Of course, it took a lot of unpaid work to create that lever for myself. I don’t know how many hours I spent taking notes on that book. But I knew that since I was reading it and taking notes anyway, I might as well kill two birds with one stone.

A lot of freelance writers I know go the newsletter route. That’s a nice lever, too: they sell sponsorships and can reach hundreds or thousands of people with a few clicks. I can’t imagine it’s a major needle-mover for most, but again: you start building where you are.

Capital: Dividend Investing vs. Selling Products

Dividend investing is the lowest-maintenance leverage ladder I can think of. Let’s say I buy $1,000 worth of a dividend fund with a high yield, like 9%. I click a button that automatically reinvests that money back into the fund. Next year, I’m collecting dividends on $1,090 instead. And on and on it goes.

Freelancing, or self-employment in general, is a famously feast-or-famine proposition. To mitigate this problem, a lot of freelancers create digital products and sell them, ideally creating passive income. Earn $5,000 to $10,000 a year passively and you’ve got something of an income moat.

The problem with selling products is that your media reach might not be where it needs to be. My audience, for example, is relatively small; if I sold a $100 product, maybe I’d get an occasional purchase. And yeah, it’s a lever because I wouldn’t have to work hard after the initial set-up phase.

The problem is that the initial set-up phase might not be worth it. Dividend investing, however, is a side hustle with almost completely predictable results. I know if I put XYZ capital into ABC fund, I can expect ~5-10% growth. As opposed to building a product I could sell, those dividends go up almost every quarter because of reinvestment. All of this without me having to do anything. To me that’s a superior lever.

Software: SaaS and AI

There’s no shortage of software you can acquire today that will extend your leverage:

- Collective is an all-in-one finance platform for freelancers

- Beehiiv is a newsletter platform

- So is Ghost

- Testimonial helps you collect testimonials from customers and clients

- Tella TV lets you record videos and lectures for repeatable products

- Grammarly in your Google Docs automatically edits for you

- Harlow is an all-in-one freelance platform

- I’ve seen freelancers use Authory for their portfolio

- I use Hypefury to schedule and optimize my twitter publishingQuillbot paraphrases lengthy research for quick digestion

AI is another hot topic and such a powerful lever that many writers fear it will replace us one day. For now, I think a healthy approach is for writers to use it, learn how to manage it, hedge against the possibility that we may become “AI Writer Editors” some day, and otherwise keep trying to beat it with our human brains.

Labor: Virtual Assistants, Ghostwriters, and Agencies

I hired a virtual assistant last month. My experience with virtual assistants before this hasn’t been great. It takes a while to onboard them and get them to figure out how to help me. Sometimes I don’t even know what tasks to assign. It often feels like I’m paying money just to train someone with no guarantee it will really help my freelancing business in the long run. The idea—to spend money so I spend less time with menial tasks—is caught up in the bottleneck of onboarding, requiring that I spend more time working. And paying money for the privilege of it.

But this time I’m sticking with the process. And you know what? It’s kind of working. I’ve outsourced a process or two that I would usually handle myself. Last week, I hit my productivity goal without feeling burned out or stressed.

Some freelance writers have enough growth that it’s time to subcontract ghostwriters or even hire them full-time to build agencies. And while “labor” is technically the oldest form of leverage in the book (not as efficient or snazzy as, say, creating an app that a million people download), it still works. You can accomplish more with a team.

Turn the First Gear

Amazon was a success story because Jeff Bezos discovered a hole in the Internet: no one was good at selling books online yet. He hammered away at that lever—sometimes doing the packing and driving down to the UPS store himself, along with his then-wife, MacKenzie—until he could add more to the Everything Store.

They say the path to success isn’t linear. And that’s true. Sometimes, all you can do is pick up the levers you see on the ground and use them to lift the next lever. Do that enough, and you have a gear. Maybe that first gear won’t move the needle much. But if you use it to turn a second gear…things eventually turn magical.