“Atomic Habits” by James Clear is an important book, offering a fresh take on building habits: leveraging small, digestible changes that become powerful results. Although I didn’t research the statistics, my estimate is that it’s been a New York Times Bestseller for roughly nineteen years and has sold roughly 7.5 trillion copies. As such, when I started reading it, it felt like an important book.

I had to take notes.

Below, you will witness the fruits of my labor. However, in the interest of digestibility, I’ve prepared a summary of James Clear’s “Atomic Habits” in three different forms. Select your level, player:

- Easy: An Infographic Summary of “Atomic Habits” (1 picture)

- Medium: Quick-hit bullet points summarizing the book (1,600 words)

- Hard: A more detailed, chapter-by-chapter breakdown (7,400 words)

James Clear’s “Atomic Habits,” Summarized in Infographic Form

Intro: the “Atomic Habits” Quick Guide

The idea behind Atomic Habits is that you can leverage small changes, via the compounding effect, to create powerful results: just like splitting atoms is technically a small thing that sets off a chain reaction that goes bonkers.

I recommend you pick up Atomic Habits on Amazon (general, non-affiliate link) because it is a comprehensive and thorough way to get through one central idea:

Behavior changes comes from a change in identity. An identity change comes not from the goals you have, but the systems you implement to inhabit them.

Below are the quick-hit takeaways that struck me as most important:

Chapter One Takeaways

- Small habits compound. Clear uses the example of British cycling to show how small, incremental improvements can add up to major results over time. See his post Marginal Gains for more.

- Small habits can be invisible at first. Imagine you have an ice cube at 20 degrees. You won’t see it melt until you get it to 32 degrees. The essential work is invisible to the rest of the world.

- Focus on systems, not goals. Build a winning system is better than setting goals. Don’t clean a room once. Learn how to become the person who cleans their room.

Chapter Two Takeaways

- To change a habit, work on a new identity. Every tiny action is a “vote” toward your new identity. No more “I’m trying to quit.” Instead, become someone who says “I don’t smoke.”

- Clear’s simple two-step process for changing your identity: Decide the type of person you want to be, then prove it to yourself with small wins. He calls these small wins “votes” toward your new identity. Terry Crews has a good example of becoming someone who liked going to the gym.

- Example from Dan: Michael Irvin used to coerce himself into the identity of a Hall of Fame wide receiver because when he’d get tired in practice, he’d ask himself if a Hall of Famer would give a little bit more. Then he did what the Hall of Famer would do.

Chapter Three Takeaways

- A new habit has four parts.

- 1) Cue. The “cue” alerts your attention to a habit and promises a reward. Think of a caveman spotting bright red raspberries.

- 2) Craving. This is your interpretation of the cue. “Red berries will be delicious if I go get them.”

- 3). Response. This is the core of the actual habit: a thought or action. “I’m getting the raspberries now.”

- 4. Reward. Self-explanatory. “These raspberries taste good.”

- Maximize all four if you want a habit to stick. 1) A habit should be OBVIOUS and its cues should surround you. 2). A craving should be ATTRACTIVE; you need to find rewards to make it worth doing. 3). When you do it, it should be as easy as possible. 4). The reward should satisfy.

These four laws then form the basis for the rest of the book, which is broken up according to each law.

Now, I’ll summarize what I found to be the most powerful points for each stage of his four-stage behavior system.

Cues: Making New Habits Obvious

- To create a good cue, first get clear and define the habit you want. Clear recommends this formula: “At 8:00 a.m., when I am in XYZ location, I will ABC.”

- To add more obviousness to a cue, add your cue to an existing habit. For example, clean the toilet when you’re warming up the shower. It’s the ideal time!

- Anne Thorndike, a doctor at Mass General Hospital in Boston, optimized how many people in the cafeteria chose water over soda. All they did was make water readily available in the environment, and soda sales dropped 11.4% while bottled water sales increased 25%. She merely added water, and put available water at more touchpoints. That was it. No coercion, no “please drink water” signs.

- Prime your environment to be full of good cues. If you want to send more thank-you notes, keep the stationery by your desk. If you want to eat more apples, keep them on the counter instead buried in the back of the fridge.

- Use context-specific clues. Matthew Walker, Ph. D., recommends using the bed only for sleeping and, uh…nevermind. Marty Lobdell noted the single habit of having a “study lamp”—a lamp students only turned on when in study mode—improved grades by a full letter.Story: in 1971, congressmen revealed that they learned over 15% of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam were heroin addicts. Lee Robins, a researcher who looked at the problem, found that when heroin users went home, 9 out of 10 kicked their addiction overnight. The key was a change in environment.

- The secret to self-control is requiring less willpower every day. If you don’t experience negative cues in the first place, your bad habits are more likely to vanish.

Craving: Making New Habits Attractive

- Use temptation bundling to associate your new habits with pleasure. Clear uses the example of Ronan Byrne, who liked Netflix, but wanted to exercise more. Byrne wrote a program that would allow Netflix to run only if he was cycling at a certain speed. He bundled his temptation to binge-watch shows into a reason to work out.

- Use this formula to temptation bundle: “After I (Current Rewarding Habit), I will (Habit I Need).”

- Humans are wired to feel rewarded by social reinforcement. Look at the crazy things we do to conform with our environment. How do you make a hard habit rewarding? Find the social context where you get tribe points for doing it.

- Find the base desire for your negative habit and address it at a sapling level before you seek out the bad habit. For example, if you’re satiated on chicken and broccoli, it’s easier to turn down pizza. If you’re hungry and pizza is a click away, though, boom: pizza.

- If you want to make a difficult task more appealing, create a ritual that gets you in the mood for it first. (Terry Crews’ “gym spa” ritual is a classic example).

Ease: Making New Habits Stupid-Easy

How to Make Good Habits Easier

- Stop waiting for perfection. Volume is better than action. Story: Uelsmann, a professor at Florida, divided his photography students into groups. One group would focus on the quantity of pictures and submit their best at the end of the year. The other group would focus on quality and submit only one. The students taking the “quantity” approach produced far superior pictures.

- “Neurons that fire together wire together” is Hebb’s Law. Repeating an action more often makes it easier and creates real brain change. Repetition makes the thing easier.

- Find whatever way you can to get your reps in. Quote: “One of the most common questions I hear is, “How long does it take to build a new habit?” But what people should be asking is, “How many does it take to form a new habit?”

- Habits, like water, seek the simplest path. Reduce friction: find automation, eliminations, or simplifications that make your desired habits easier to perform. Example: cleaning toilet while waiting for the shower to clean reduces friction. You’re dirty anyway.

- Use a “two-minute rule,” or habits that can be performed in two minutes,” to introduce ease into a new habit. If you can’t get yourself to jog, you can at least get your shoes on. “Standardize before you optimize,” says Clear. Establish the habit via easy reps, THEN improve upon it.

- Prime your environment to make habits more natural. If you want to drink more water, put out water bottles and hide the soda.

How to Make Bad Habits Harder

- Automate away bad habits whenever possible, as well. A supply store owner in the 1800s was having trouble with employee theft until he found Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier, which automatically locked the cash and receipts after a transaction. The bad habits disappeared immediately. You might consider: only using small plates to reduce portion size, for example.

- Add friction to bad habits. Clear, for example, has his assistant take away his social media passwords until the weekends.

Reward: Making New Habits Satisfying

- Story: sanitization efforts in Pakistan were going horribly until a public health worker invested in pleasant-smelling, pleasant-feeling soaps. Diarrhea fell by 52 percent.

- “What is rewarded is repeated.”

- But! A problem. Bad habits are highly rewarding in the short-term, and good habits’ rewards are more long-term. Your challenge is to add gratification to the good habit in the immediate short-term.

- Give yourself short-term rewards by creating a private “loyalty program.” For example, put $5 in a jar when you didn’t buy that drink. This is a visual reward. We give kids gold stars when they do something good. Buy YOURSELF some gold stars. Make the IMMEDIATE term rewarding.

- Create visual cues for your progress. Story: In 1993, a bank in Canada hired a 23-year-old stockbroker named Trent Dyrsmid. Not much might have been expected from him, but he made fast progress thanks to a simple daily habit. He began each morning with two jars on his desk. One: 120 paper clips. The other empty. Once he made a sales call, he’d drop a paperclip into the empty one. He would keep dialing until the other jar was full. He was soon making tons of sales because he had a little reward each time he made the sales call, as well as a way of measuring his progress.

- Track yourself. Habit tracking makes a habit obvious and also gives you a reward.

- Video game-ify your reward system. Find ways to make yourself “level up” for everything you do.

- Consider an accountability partner, with a “signed contract,” to help add social friction to failing in your habits.

There you have it. That’s the book in a nutshell. Enjoy your successful life.

What’s that? You want me to flesh out those details?

Oh, fine. Let’s do another 8,000 words.

Chapter-By-Chapter Breakdown

- Chapter 1. The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

- Chapter 2. How Your Habits Shape Your Identity

- Chapter 3. How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

- Section 1: The 1st Law – Make It Obvious

- Chapter 4. The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

- Chapter 5. The Best Way to Start a New Habit

- Chapter 6. Motivation is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More

- Chapter 7. The Secret to Self-Control

- Section 2: The 2nd Law – Make It Attractive

- Chapter 8. How to Make Habit Irresistible

- Chapter 9. The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

- Chapter 10. How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

- Section 3: The 3rd Law – Make it Easy

- Chapter 11. Walk slowly, But Never Backward

- Chapter 12. The Law of Least Effort

- Chapter 13: How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule

- Chapter 14: How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

- Section 4: The 4th Law – Make it Satisfying

- Chapter 15. The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change

- Chapter 16. How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day

- Chapter 17. How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything

Chapter 1. The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

Clear starts with the British cycling story; you can find more here. In short: when Dave Brailsford took over British cycling, he looked for “marginal gains” everywhere—the 1% little changes you can make that lead to profound changes over time. That included the small things that had little to do with cycling, like learning how to wash their hands better so they could avoid sickness. But of course, if you toss a bunch of these tiny habits into a singular goal, they start to add up. British cycling became dominant.

Clear elaborates on the value of seeking exponential gains:

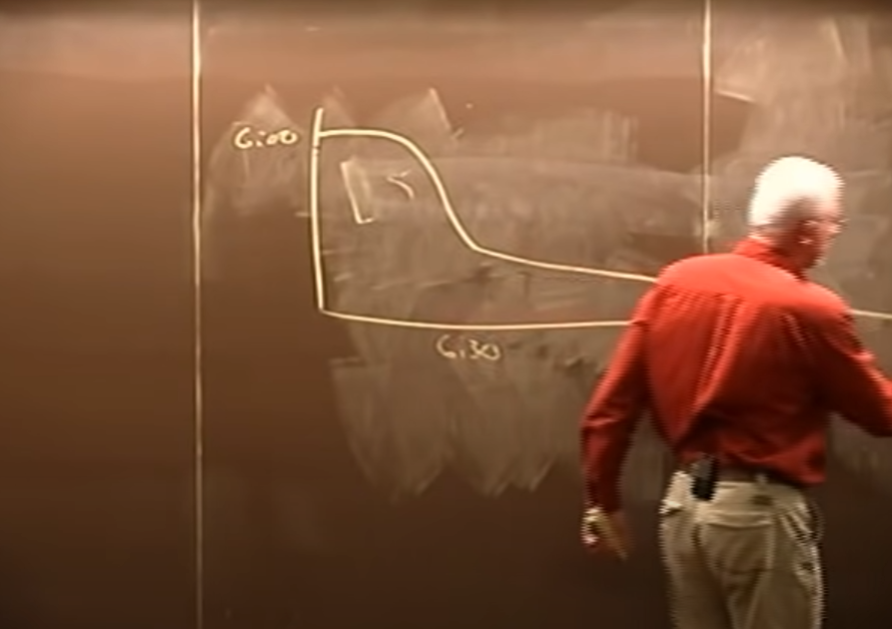

- Metaphor of the ice cube. Try to melt it a degree at a time, and it works…but you won’t see progress until 32 degrees.

- Plateau of Latent Potential. Habits don’t effect change until you overcome this plateau. P. 22 for the drawing.

- Quote: San Antonio Spurs in their locker room. “When nothing seems to help, I go and look at a stonecutter hammering away at his rock, perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred and first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not that last blow that did it—but all that had gone before.”

Focus on systems, not goals. If you’re building a business, a million dollars is your goal, but the system is: people you hire, the customers you acquire, etc.

- Problem #1: Winners and losers have the same goals. Goal setting suffers from survivorship bias. Successful people always have big goals, but is that really what’s driving success?

- Problem #2: Achieving a goal is only a momentary change. Goal to clean a room once doesn’t do anything. Designing a system or habit to keep the room clean is lasting change.

- Problem #3: Goals restrict happiness. “Once I achieve this, I’ll be happy” mindset. Systems-first gives you permission to be happy right now.

- Problem #3: Goals are at odds with long-term progress. The purpose is to win the game, creating a yo-yo effect.

Chapter Summary:

- Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement.

- Habits can work for you or against you, so it’s worth taking command and learning how to do that.

- Small changes require some time before they cross a notable threshold for noticeable improvement. See: Plateau of Latent Potential.

- Systems, not goals.

- “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

Chapter 2. How Your Habits Shape Your Identity

Fun fact: the word “identity” comes from essentitas, which means being, and identidem, which means repeatedly. So your identity is malleable; it is what you choose to repeatedly be.

There are two ways to start changing your habits:

- Outcome-based habits. “I want to lose weight.” “I want to win a championship.” This is generally where you build goals, not systems.

- Identity-based habits. A smoker who says “no thanks, I’m trying to quit” is still taking on the identity of a smoker who’s merely trying to quit. “No thanks. I don’t smoke.” Is a habit that based on identity-level change.

Example: A man named Brian Clark chewed his fingernails. He chose the “identity”-level change. He went to get a manicure. After a compliment from the manicurist, he became proud of his fingernails. By taking pride in those fingernails, he stopped chewing them completely and hasn’t looked back.

It’s one thing to say I’m the type of person who wants this. It’s something very different to say I’m the type of person who is this.

-James Clear

The Two-Step Process to Changing Your Identity (p. 36)

James Clear considers habits to be little “votes” for your identity. Every time you develop a habit, you’re casting a new vote for your basic belief about who you are.

His simple, two-step process:

- Decide the type of person you want to be.

- Prove it to yourself with small wins.

Rather than setting the goal of “I want to win teacher of the year,” you might instead set an identity-level goal of “I want to be a teacher who always gives each student the time and attention they need.” What kinds of habits would that teacher have?

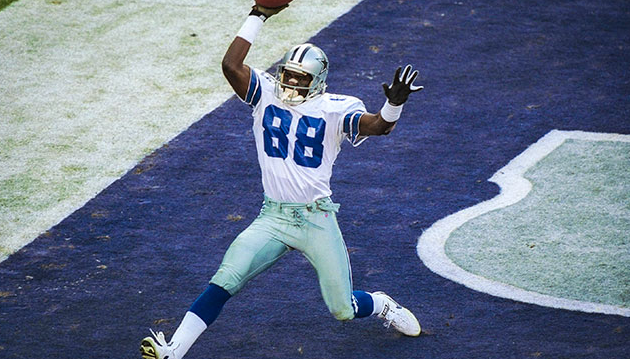

An example from Dan: I remember reading somewhere that Michael Irvin, wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys, would practice himself to exhaustion. Then, when it came time to make a decision (like whether to keep going), he would ask himself, “What would a hall of famer do right now?” He eventually made it to the Hall of Fame.

Identity change is the North Star of habit change.

-James Clear

Chapter Summary:

- There are three levels of change: outcome change, process change, and identity change.

- The most effective way to get started is to focus not on achievements, but on becoming the type of person who achieves those things.

- Every habit is a “vote” for your new identity. Bad habits do the same against you.

- The real reason for good habits is because they change your beliefs about yourself.

Chapter 3. How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

Key point: Behaviors followed by satisfying consequences are more likely to be repeated.

James Clear opens this chapter up with a study. In 1898 a researcher named Edward Thorndike would put a cat in a puzzle box. They only had to do something simple, like pull a lever, to open the door out, where they were greeted by a reward.

He watched immediate improvement as cats figured out what to do. Cats would take minutes at first. Then they slowed down: 30 seconds, 90, 60, 15, 28…eventually, they were completing it under ten seconds.

His conclusion? Rewarding yourself improves your habits and reinforces them.

This is the feedback loop behind all human behavior: try, fail, learn, try differently. With practice, the useless movements fade away and the useful actions get reinforced. That’s habit forming.

-James Clear

Think of the brain as IFTTT: if this, then that.

The Four Key Steps

The process of building a habit is four steps in two phases.

Problem Phase:

- Cue: The sign that a reward is around. For example, a caveman seeing a bunch of red raspberries would identify the color as a cue.

- Craving: The interpretation of the cue.

Solution Phase:

- Response: This is the core of the actual habit, a thought or action. “A habit can only occur if you are capable of doing it. If you want to dunk a basketball but can’t jump high enough to reach the hoop, well, you’re out of luck.”

- Reward: The end of the loop, the satisfaction to the craving established. Rewards teach us remembering which actions (or responses) are with repeating in the future.

“If a behavior is insufficient in any of the four stages, it will not become a habit,” says Clear. No cue, and the habit never starts. No craving and there’s no impetus for the response. No reward and your brain has no reason to create the craving in the future.

Example of a habit:

- Cue: Phone buzzes with a new text message. Chapter Five Talks about Cue optimization.

- Craving: You have to know what it says.

- Response: You grab the phone and read it.

- Reward: You satisfy the craving of the information. Cue-response becomes grabbing your phone when you hear the text alert.

(Note from Dan: ever notice you pick up your own phone when someone else’s goes off? I do this.)

The keys to optimizing all four:

- Cue: Make the cue OBVIOUS.

- Craving: Make the craving ATTRACTIVE.

- Response: Make the response behavior EASY.

- Reward: Make the reward SATISFYING.

Chapter Summary:

- The purpose of habits is to reach efficient solutions to problems without expending energy and effort, or as little as possible.

- To build a habit, make it obvious, make it attractive, make it easy, and make it satisfying.

Section 1: The 1st Law – Make It Obvious

Chapter 4. The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

Clear demonstrates a bunch of examples of “unconscious competence” from people in professions.

Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.

-Carl Jung

Pointing and calling: In the Japanese rail system in Tokyo, the conductors have a strange habit. As they run the train, they point to different objects and call out commands. For example, they’ll look at a signal, point to it, and say “signal is green.” They name every key detail out loud to help confirm it, for safety reasons.

Apparently it works, reducing errors “by up to 85 percent” and accidents by 30 percent. The key: turning unconscious habits into conscious ones, where they can be controlled. When people point at a light, they may be more likely to notice if it’s the wrong color.

“I’ve got my keys. I’ve got my wallet. I’ve got my glasses. I’ve got my husband.”

-James Clear’s wife, before leaving the house

(Note from Dan: I wasn’t a huge fan of this chapter, as the point seems to be that we have unconscious habits in our lives and we need to identify what they are to improve. I’ll skip the chapter takeaways here.)

Chapter 5. The Best Way to Start a New Habit

Study: Researchers broke people into three groups to see which method was best for inspiring them to exercise. A control group, a motivation group (that received some motivation without tracking exercise), and a motivation + planning group. Not too surprising, the group that created a system (i.e., I will do 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on XYZ day) was by far the best. They exercised at least once per week 91% of the time; the other groups were at about a third.

Included with that planning, Clear argues, were cues of time and location. For instance, the plan included something like “at 8:00 a.m., when I am in XYZ location, I will work out.”

“Hundreds of studies have shown implementation intentions [Dan’s note: knowing how, when, and where you’re going to take on a haibit] are effective for sticking to our goals,” says Clear.

Many people think they lack motivation when what they really lack is clarity.

-James Clear

Key point: people don’t feel unmotivated; they simply don’t have detailed enough plans for implementing a new habit.

“Just do it” may work for Nike, but it’s terrible advice if you want a habit to stick.

ACTION STEP: Clear advocates building a new habit by filling out the blanks in this sentence:

I will [BLANK] at [BLANK TIME] in [BLANK LOCATION].

For example, you want to be nicer to your wife? Make that “I will make my wife a cup of tea at 8 a.m. in the kitchen.”

The Diderot Effect: Stackin’ habits. French Philosopher Denis Diderot was poor until Catherine the Great bailed him out by buying his library for about $150,000 today. Diderot paid for his wedding and bought himself a fancy silk robe. But suddenly, everything he owned seemed to pale in comparison to the robe. He upgraded his mirror. He bought sculptures. “The Diderot Effect” is when one habit stacks upon your previous action.

Emotional momentum.

You can use this to your advantage by stacking your new habit on an old habit.

BJ Fogg (author of Tiny Habits) uses this habit stacking formula:

After I CURRENT HABIT, I will NEW HABIT.

It’s a neat little trick that lets you take advantage of your own Diderot effect for positive consequences rather than negative ones.

Keys to optimizing your cues:

- Get specific with habit design by defining your action, when it will happen, and where it will happen.

- Ease into the new habit by using an already-existing habit.

- Make sure your cues match your goals. I.e., use a daily habit to “stack upon” for new daily habits; a once-a-week habit isn’t good for that.

Chapter Summary:

- The first law of behavior change is make it obvious.

- Common cues for new habits are time and location.

- Stack upon existing habits to make cues easier and ride that momentum.

- Implementation intention formula: “I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].”

- Habit stacking formula: “After I [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].”

Chapter 6. Motivation is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More

Example: Anne Thorndike, a doctor at Mass General Hospital in Boston, optimized how many people in the cafeteria chose water over soda. All they did was make water readily available in the environment, and soda sales dropped 11.4% while bottled water sales increased 25%. She merely added water, and put available water at more touchpoints. That was it. No coercion, no “please drink water” signs.

This chapter is all about environment for cues.

People often choose products not because of what they are, but because of where they are.

-James Clear

It happens everywhere. Items at eye level tend to get more sales, which is why those locations in the store are more expensive.

We like to think we’re in control, when really we’re choosing from the environment we’re presented with.

How to Design Your Environment for Success

Dutch researchers noticed that in homes with more obvious electrical meters, they tended to use about 30% less energy, despite being the same size as their counterparts. “What gets measured gets managed.”

Another example: When an airport cleaning staff installed stickers that looked like flies into urinals, it made people aim their “streams” that way. The result was 8% reduction in bathroom cleaning costs. No “please don’t pee on the floor” signs.

James Clear used his environment to eat more apples. Rather than bury them at the bottom of the fridge, he’d put them right out in the kitchen counter in a big display bowl. “Almost like magic, I began eating a few apples each day simply because they were obvious rather than out of sight.”

Tips for enhancing your environment:

- If you want to send more thank-you notes, keep the stationary by your desk.

- If you want to drink more water, fill up water each morning and put them around the house.

Context Cues

How often do you go to the gym and fail to workout? Chances are, your willpower is expended before the gym. Once you’re there, the environment is such that all context cues pretty much determine that you’ll work out. The willpower battle is fought beforehand.

Note from Dan, who is riffing now: I remember Terry Crews talking about how he got himself to work out two hours a day. He said he would go to the gym every day and treat it like a spa. If he didn’t want to work out, he’d go there and read a magazine. He started associating it with good feelings, and of course, since he was constantly there, guess what happened? He would work out.

One way they help insomniacs is to tell them not to go into the bed until they were tired. Matthew Walker of Why We Sleep also advocates using the bed for sleeping and…other. But not reading. Not looking at your phone. The context cue of “bed=sleep” helped the insomniacs get to sleep easier.

This is also indicated in “Study Less, Study Smart,” in which he notes a study where college students used a “study lamp” in their dorm rooms. The study lamp was essentially an on/off environmental cue. When it was on, you were studying. When it was off, you weren’t. People who used the lamp improved by one full letter grade, just by optimizing their environment.

Takeaways:

- Create a “work cue” to associate habits with the environment. If you must work at the same computer you also play at, for example, use a “study lamp” to denote when it’s work time. Otherwise, don’t play at the office and don’t work in the kitchen. Maintain the environment for the appropriate habits.

- Small changes in context can lead to large changes in behavior over time. (i.e., electrical meters in the home led to decreased electricity consumption).

- Every habit begins with a cue. You are more likely to notice cues that stand out.

Chapter 7. The Secret to Self-Control

Story: in 1971, congressmen revealed that they learned over 15% of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam were heroin addicts. Lee Robins, a researcher who looked at the problem, found that when heroin users went home, 9 out of 10 kicked their addiction overnight.

What gives?

“Robins revealed that addictions could spontaneously dissolve if there was a radical change in the environment.”

One problem is cue-induced wanting: simply being exposed to the cue itself, or the habit, makes you want it. For example, if you’re on a diet and you watch Claire Saffitz videos for baking a birthday cake, you’re gonna have a bad time.

If it’s a good idea to make your cue obvious to make a new habit appear, then you’ll want to make your old cue invisible if you want an old habit to disappear. Master the cues.

Key takeaways:

- The ones who appear best at self-control are the ones who need to use it the least. It’s easier to practice self-restraint if you don’t have to…restrain yourself.

- To cut out the roots of a bad habit, find ways to reduce exposure to cues in the environment.

Section 2: The 2nd Law – Make It Attractive

Chapter 8. How to Make Habit Irresistible

Study: Dutch scientist Niko Tinbergen and herring gull experiment. Gulls would peck at a small red dot on their parents’ beak when they wanted food. The experiment found out that this worked for obviously fake red dots on beaks. The birds would still peck. And when they made larger dots or added dots, birds went crazy trying to peck them.

Essentially the gist of this study is that if you use an instinctual habit with an animal and blow it up to abnormal proportions, you can create supernormal stimuli.

An example of this is in humans. We might have evolved to enjoy the sweetness of a few raw berries we find in a bush; we create cakes, however, and give ourselves supernormal stimuli that can completely rewire us and change our bodies.

The Dopamine-Driven Feedback Loop

You can measure the size of your craving by measuring dopamine. When scientists in 1954 blocked the release of dopamine in rats, they noticed the rats lost all will to live. They wouldn’t eat, have sex, or do anything. They eventually died of thirst. Yikes.

Erasing dopamine erased the “desire” portion of a craving. We think of dopamine as reward, but it’s really motivation -> reward.

“Habits are a dopamine-driven feedback loop,” says James Clear. But dopamine isn’t just a reward hormone: it’s an anticipation hormone. Gambling addicts have a dopamine spike not after they win, but in the moments before.

“It is the anticipation of a reward—not the fulfillment of it—that gets us to take action.”

Clear also notes that “your brain has far more neural circuitry allocated for wanting rewards than for liking them.”

“We need to make our habits attractive because it is the expectation of a rewarding experience that motivates us to act in the first place.”

To do this, Clear recommends a strategy known as temptation bundling.

Temptation Bundling

Example: Ronan Byrne was a student in Dublin. He liked Netflix, but wanted to exercise more. He wrote a program that would allow Netflix to run only if he was cycling at a certain speed.

He turned his bad temptation (Netflix) to a positive habit (stationary cycling).

“Temptation bundling works by linking an action you want to do with an action you need to do,” writes Clear.

Another example: ABC’s Thursday night lineups often encouraged viewers to make popcorn and drink red wine, make an evening of it. They bundled the temptation they needed (viewership) with what they knew viewers already wanted (chilling out on Thursday night).

“You’re more likely to find a behavior attractive if you get to do one of your favorite things at the same time.”

Example: only listening to your favorite podcast when at the gym.

It’s known as Premack’s Principle, named after professor David Premack: more probable behaviors will reinforce less probable behaviors.

James Clear provides a formula for creating temptation bundles: “After I (Current Rewarding Habit), I will (Habit I Need).”

Takeaways:

- 2nd Law of Behavior Change: make it attractive.

- Dopamine and reward anticipation are what emote us into action. Not the reward itself. The anticipation of reward is therefore vital for getting yourself to do a new habit.

- Use temptation bundling in this chapter to make your habits more attractive.

Chapter 9. The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

Example: A strange Hungarian man named Laszlo Polgar tried an experiment: he thought that all talent was not innate, but in fact the result of deliberate practice. He sought out a wife to “jump on board” with his experiment. He wanted to raise kids to become chess prodigies. He would dedicate these children’s lives to chess.

All three daughters became good at chess. Susan was beating adults by the age of five. Sofia was a grandmaster at a young age. Judit became the youngest grandmaster of all time, even younger than Bobby Fischer.

All three children grew up in the chess culture of Polgar’s design. The lesson, Clear says: “whatever habits are normal in your culture are among the most attractive behaviors you’ll find.”

The Seductive Pull of Social Norms

It’s a natural reward to do things that society/culture pulls us to do, which can make just about any habit rewarding if it’s socially reinforced.

Key: join a culture where your desired behavior is normal behavior.

There are three key groups in particular we follow:

- The close. Proximity has a powerful effect on our behavior. Personal example from Dan: my cousin from Illinois said that after spending time with us in Wisconsin, his sisters would recognize how he started picking up our accent. Person’s chances of becoming obese increased by 57% if they had a friend who became obese.

- The many. Solomon Asch studies from 1950s: social conformity experiments. People would answer with objectively incorrect answers if they saw that other people were doing the same. Check out this elevator experiment where people face the wrong way because other people are doing it. That’s more powerful than hypnosis.

- The powerful. Michael Jordan is drinking Gatorade; maybe I should.

Chapter Takeaways:

- We adapt to our culture. You can make almost any behavior rewarding if you get social points and conformity from it.

- We tend to adopt habits that earn us praise because we have a primordial desire to fit in with the tribe.

- The most powerful: close proximity, the madness of crowds, and powerful figures.

- If you want to make any behavior rewarding when it’s objectively not (ahem exercise), join a group where it’s the norm.

Chapter 10. How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

Story: James Clear was in Turkey with a friend who had quit smoking, despite a group of friends where half of them did smoke. He had read “Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking.”

This book is interesting because it basically uses logic to break down all of your emotional arguments for not quitting. It says things like “You think you’re quitting something, but you’re not quitting because cigarettes are just hurting you.” Or “You think you need it to be social but lots of people are social without smoking at all.”

The goal is to get to the bottom of the emotional attachment you have to a habit until you see it for how ridiculous it is.

Where Cravings Come From

Look around and you’ll see anything we do is connected to an intrinsic human motivation. Love? Tinder and dating apps. Hunger? Doritos and Pizza Hut. Status chasing? Video game rewards. Says Clear: “your habits are modern-day solutions to ancient desires.”

However, some cravings develop differently around the same motivation. One person might reduce stress through smoking; another by going on a run. Habits are all about associations, writers Clear, and “every time you perceive a cue, your brains runs a simulation and makes a prediction about what to do.”

Cue: you notice the stove is hot. I’ll get burned so I’ll avoid it.

Cue: Traffic light is green. Time to step on the gas.

Cue: cigarette. Well, what’s the deal here? Someone might see status, friendship, and relaxation. Someone else might be repulsed by the smell and the idea of what it would do to their lungs.

The cause of your habits is actually the prediction that precedes them.

To solve bad habits, address the underlying motives that create the disparity between your feeling and your reward.

How to Reprogram Your Brain to Enjoy Hard Habits

Clear recommends highlighting the benefits of your difficult but healthy habits. For example: if exercise is a drag, look for the benefit of building stamina. Or if you’re saving money and struggling, try to think of it as wealth-building instead.

Clear also recommends a sort of “pregame ritual” approach to habits.

Takeaways:

- The inversion of the “2nd law of behavior change” is to make it unattractive.

- Find the deeper causes of your surface-level unhealthy cravings and address that need in a healthier way with a habit replacement.

- To associate a difficult habit with good feelings, create a motivation ritual that gets you into the “mood” before doing the habit by doing something you enjoy.

Section 3: The 3rd Law – Make it Easy

Chapter 11. Walk slowly, But Never Backward

Story: Uelsmann, a professor at Florida, divided his photography students into groups. One group would focus on quantity of pictures and submit their best at the end of the year. The other group would focus on quality and submit only one.

The students taking the “quantity” approach produced far superior pictures.

Difference between motion and action: action is superior, because it is self-correcting. You do something, then aim. Motion can be spinning your wheels, such as planning something, but not doing it and learning from real-world results. You want action.

How Long does it Actually Take to Form a New Habit?

“Neurons that fire together wire together.” Hebb’s Law. Repeating an action makes it easier and creates real brain improvement. You have to repeat things for them to become easy and natural.

When scientists analyzed the brains of taxi drivers in London, they found that the hippocampus—a region of the brain involved in spatial memory—was significantly larger in their subjects than in non-taxi drivers. Even more fascinating, the hippocampus decreased in size when a driver retired.

Your brain is as malleable as muscle. Use it or lose it.

One of the most common questions I hear is, “How long dos it take to build a new habit?” But what people should be asking is, “How many does it take to form a new habit?”

As in “how many reps.” Clear argues that action is far more important than time in building habits. Reps, reps, reps, volume, volume volume. “Atomic Habits” helps that with small dedicated actions, because small actions are easy to repeat.

Takeaways:

- The most effective form of learning is practice, not planning.

- Focus on action rather than motion. Learn as you go. Don’t optimize without real world practice.

- Habit formation is about repetitions, not time.

Chapter 12. The Law of Least Effort

Story: Clear relates an analysis that suggests that agriculture spread based on the shapes of continents, suggesting that geographical ease is partially responsible for how civilization developed.

“Look at any behavior that fills up much of your life and you’ll see that it can be performed with very low levels of motivation.”

But what about habits that aren’t so easy? Like dieting to lose weight? You make them as easy as possible.

How to Achieve More with Less Effort

Environment design: Start by designing an environment conducive to your new habit. In Chapter 6, it talked about making cues more obvious. But what about making actions easier?

For example, you might place a new habit somewhere in a daily routine to piggyback on the established habit. “Habits are easier to build when they fit into the flow of your life.” Join the gym on your preexisting route, not the far away one, for example.

Story: Japanese electronic manufacturing firms in the 1970s. They emphasized “lean production,” relentlessly looking to remove waste from the production process. Something as small as a worker twisting to reach a tool was seen as wasted movement. Over time, it eventually took Americans three times as long to build television sets as it did in Japan.

Reduce friction, the way dating apps reduce friction in meeting new people, the way grocery delivery services reduce the friction of buying food.

- Automate

- Eliminate

- Simplifiy

Prime the Environment for Future Use

Story: Oswald Nuckols, an IT developer from Natchez, MS. He “resets the room” every time he’s done using it. Or when he takes a shower, he wipes down the toilet while it’s warming up.” (He notes it’s the perfect time to do it, because you’re about to clean yourself anyway.)

Examples of priming environment:

- Make health foods convenient with meal prep

- Keep an exercise bag full of everything you need for the gym to minimize prep time

You can also make bad behaviors difficult. Too much TV? Try unplugging it after you’re done using it. Add friction to the next decision to watch TV.

Takeaways:

- Humans follow the “Law of Least Effort.” Think of water seeking the simplest path.

- Create an environment that maximizes the ease of your desired habits and adds friction to the undesired ones.

- “Ritualize” some behaviors, like the guy who cleans the toilet when the shower is warming.

- Prime your environment to make future actions easier.

Chapter 13: How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule

Story: Twyla Tharp. One of the great dancers/choreographers. She credits her success to daily habits. She starts with a ritual: 5:30 a.m., she puts on her workout clothes. Hails a taxi, goes to the gym, works out two hours. “The ritual is the cab,” says Tharp. Just getting to that cab is the most important part.

The success of Tharp’s method is building a ritual that’s easy to do that leads to something difficult to do. Says Clear: “Habits are like the entrance ramp to a highway.” They should lead you down the right paths so that you naturally move into the next (and desired) behaviors.

Clear calls these little moments decisive moments in your day. One little choice can branch off into other similar choices.

The Two-Minute Rule

To make any habit easier, scale it down into two minutes. “Read before bed each night” becomes “read one page.” “Run three miles” becomes “tie my running shoes.”

To create a habit, reinforce it by doing it consistently, even if it only takes two minutes per day. “The habit must be established before it can be improved.”

Takeaways:

- Habits can be completed in a few seconds, but that decision can affect your behavior for hours afterward.

- The Two Minute Rule: distill your habit down to its easiest form to reinforce the identity of that behavior. Establish the habit of doing something before you optimize/improve it

- “Standardize before you optimize”

Chapter 14: How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

Story: Victor Hugo was facing a tight deadline, with his publisher demanding a new book. But Hugo had been procrastinating. He took all of his clothes and asked his assistant to lock them away, except for a large shawl. Anything he needed to go outdoors during the fall and winter was removed from him, leaving him in his study where he worked on The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He finished on time.

If making it easy helps new habits, making something hard hurts bad habits.

Examples: you can voluntarily add casinos to ban you to avoid gambling. You can leave cash and credit cards at home to avoid being tempted with fast food drive-thrus. “The key,” says Clear, “is to change the task such that it requires more work to get out of the good habit than to get started on it.”

How to Automate a Habit and Never Think About It Again

Story: James Henry Patterson, who opened a small supply store for coal miners in Ohio in the 1800s. He had good customers coming in, but didn’t make money. He discovered employees were stealing from him.

It was the 1800s, after all; there wasn’t good security tech available. One day, Patterson came across an ad for an invention: Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier. This automatically locked the cash/receipts inside after a transaction. Patterson bought two, and theft disappeared overnight. His store started making a profit immediately.

He loved it so much, in fact, that he bought the rights to the invention and opened up a new company. It went gangbusters.

He’d stumbled on something important: the best way to break a bad habit is to make it impractical to do. So the advice is to seek out onetime actions that lock in good habits, such as:

- Eating off of smaller plates every time to reduce portion size

- Buy a better mattress to sleep better

- Remove a television from a bedroom

- Unsubscribe from junk emails

- Set your phone to silent

- Delete unproductive apps off your phone

- Get a dog

- Set up automatic savings in your bank account

Civilization advances by extending the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them.

-Alfred North Whitehead

For example, Clear experimented with a time management strategy to cure his social media habit. He’d have his assistant reset the passwords on all his social media accounts during the week. So all week, he’d work without distraction. On Friday, he got the passwords back.

Takeaways:

- Automate the difficulty of bad things, automate the convenience of good things

- Look for one-time choices (like automatic investment/savings) that lock in future behavior

Section 4: The 4th Law – Make it Satisfying

Chapter 15. The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change

Story: Public health worker goes to Pakistan and sees that the sanitization efforts are terrible. In particular, handwashing meant bad habits. So he decided to get more pleasurable, rewarding soap. Rapid shift in health: diarrhea fell by 52 percent, for example.

They’d stumbled onto the fourth law: make it satisfying. Another example: chewing gum didn’t take off until Wrigley brought flavors like Spearmint and Juicy Fruit.

What is rewarded is repeated.

The Mismatch Between Immediate and Delayed Rewards

But! A problem. You want to skip the Big Mac (rewarding) for the long-term reward of being fit (punishing in the short-term). As Clear says, “the human brain did not evolve for life in a delayed-return environment.” So “the way your brain evaluates rewards is inconsistent across time.” Cake is bad long-term, but immensely rewarding short-term. So we have the mechanism for a bad habit.

It almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. . . . Often, the sweeter the first fruit of a habit, the more bitter are its later fruits.

–Frederic Bastiat

So Clear recommends revising it: to make something satisfying, make it clear that the habit that is immediately rewarded gets repeated, while what is immediately punished gets avoided.

Add immediate pleasure to the habits you want to cultivate.

How to Turn Instant Gratification To Your Advantage

Key: you want to feel successful. This is an immediate hit of “reward feeling.”

Habit stacking, which we covered in Chapter 5, ties your habit to an immediate cue, which makes it obvious when to start. Reinforcement ties your habit to an immediate reward, which makes it satisfying when you finish.

-James Clear

For example, say you want to get rid of a habit, such as “no alcohol this month.” But nothing happens when you skip alcohol! Where’s the reward?

Create a “loyalty program” for yourself. Give yourself the feeling of accomplishment when you avoid spending that $5 on a drink. This is the feeling of “success” that rewards the avoidance.

For example, a James Clear reader used a setup of “Trip to Europe” savings account rather than eating out. Every time they avoided it, they put $50 toward it. After a year, they had a “free” vacation.

Obviously there are limits. A bowl of ice cream as a reward for exercise doesn’t align with your new identity of being in shape.

Takeaways:

- 4th Law of Behavior Change is make it satisfying with a reward.

- We repeat what is immediately rewarded. We avoid what is immediately punished.

- Find a way to make a habit, even an avoidance habit, successful, such as by creating a savings account you contribute to every time you avoid the habit.

Chapter 16. How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day

Story: In 1993, a bank in Canada hired a 23-year-old stockbroker named Trent Dyrsmid. Not much might have been expected from him, but he made fast progress thanks to a simple daily habit.

He began each morning with two jars on his desk. One: 120 paper clips. The other empty. Once he made a sales call, he’d drop a paperclip into the empty one. He would keep dialing until the other jar was full.

“Within eighteen months, Dyrsmid was bringing in $5 million to the firm. By age twenty-four, he was making $75,000 per year—the equivalent of $125,000 today.” He soon got a six-figure job with another company.

Clear calls it the Paper Clip Strategy. It’s a way of creating a little “chime” (like you might get a chime from a video game when going up a level) to track your progress and give reward to difficult habits.

How to Keep Your Habits on Track

Jerry Seinfeld technique: “never break the chain” in writing jokes, by marking a calendar with an X every day. Why do this? Some specific benefits noted by Clear.

- Habit tracking makes a habit obvious. Recording your last action cues another one. Also, the mere act of tracking helps spark the urge to change it, such as a daily food log. Habit tracking also helps you avoid lying to yourself, or quitting when you’ve “done enough.”

- Habit tracking is attractive. You can see visual proof of how far you’ve come.

- Habit tracking is satisfying. Like leveling up in video games. Many people complain that it’s adding two habits to also track, but if it helps you feel a sense of reward, how much of an added burden is it really?

How to Recover Quickly When Your Habits Break Down

James Clear’s rule is “never miss twice.” Remember: the goal is casting small votes toward an identity, so you want to get back to high frequency ASAP.

“Anyone can have a bad performance, a bad workout, or a bad day at work…”

But when successful people fail, they rebound quickly. The breaking of a habit doesn’t matter if the reclaiming of it is fast.

–James Clear

Or:

The first rule of compounding: never interrupt it unnecessarily.

-Charlie Munger

This, Clear notes, is why the bad workouts are often the most important ones. Bad workouts maintain the compound gains you were working on.

Knowing When (And When Not) To Track a Habit

You need accurate tracking. For example, does a restaurant really know its chef is good by the amount of foot traffic? Track what matters.

There’s also a dark side to tracking a particular behavior: being driven by the measurement rather than the original purpose. Don’t focus on working long hours. Focus on getting meaningful work done. Goodhart’s Law states when a measurement becomes the goal, it ceases to become a good measure.

Takeaways:

- “Making progress” and visualizing it is a key way to give yourself a reward and to make a habit satisfying.

- A habit tracker like an X on the calendar can be a useful tool for measuring.

- Never miss twice. If you break a bad habit, go back to it immediately. These instances are the most important ones.

Chapter 17. How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything

Story: The idea of Roger Fisher, a prominent strategist for avoiding nuclear war, to create a nuclear code capsule that could be lodged near a person’s heart. For the president to launch a nuclear war, the argument was, they’d have to kill a person face-to-face first.

Lesson: “Pain is an effective teacher.” We avoid what is immediately painful. Says Clear: “To be productive, the cost of procrastination must be greater than the cost of action.”

The Habit Contract

Easy way to add immediate cost to any bad habit. As governments add regulations to deter bad behavior, you can do the same to your life.

Example: Bryan Harris, an entrepreneur from Nashville. He wanted to lose weight. He wrote up a habit contract between him, his wife, and his trainer. He set a goal of 200 pounds at 10% body fat. Then he created three phases:

- Phase #1: “Slow carb diet” in Q1.

- Phase #2: Macronutrient tracking program in Q2.

- Phase #3: Refine and maintain diet in Q3.

Then he wrote out the daily habits, such as a food journal.

Finally, he created a punishment for if he fails. For example, he would have to give his trainer $200 if he missed a day of logging food.

All three parties signed the contract, and it worked.

You don’t have to be as strict; Margaret Cho has a “song a day” challenge with a friend.

Takeaways:

- Find accountability rules and “regulations” to make a bad habit unsatisfying.

- Add pain and friction to habits you want to avoid. For example, “Thomas Frank, an entrepreneur in Boulder, Colorado, wakes up at 5:55 each morning. And if he doesn’t he has a tweet automatically scheduled that says ‘It’s 6:10 and I’m not up and I’m lazy!” and offers to pay people for it via PayPal.

If you made it this far, I’m not going to bother with the conclusion. But in the interest of rewarding you for your good habit of reading this blog, here’s a fun video.

Do you like lots of words like these? Do you want lots of words like these on your website or blog? Reach out to me to see if we can’t work out a content strategy to promote your brand.