How to Study Less and Remember More

If someone asks you how to become more disciplined at work, or study hard for a test, what we usually tell them? Buckle down. Put your nose to the grindstone. Spend an hour a day studying, and you’ll get there.

It’s the advice we give to anyone who needs to work harder and get better results: higher grades, more income, better memory retention.

It’s the way most people study or work.

It’s also the worst way to study or work.

Allow me to explain. To do so, I’ll use a bunch of highlights from one of the best videos on YouTube, Marty Lobdell’s “Study Less Study Smart” lecture.

What’s so great about it? It isn’t another boring lecture with basic tips like “study one hour a day” or “buy yourself a calendar.” It’s a lecture about human nature. Mary doesn’t tell you what he thinks you should do to improve your discipline and memory retention. He teaches what works. In actual living, breathing people.

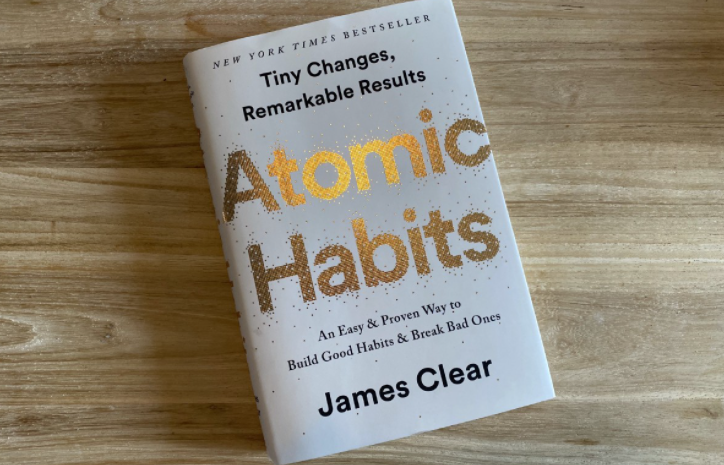

Although Lobdell’s audience was a group of students looking to learn better study habits, you can apply these same lessons to anything you want to accomplish.

What follows here is less a blog post and more a summary of Marty Lobdell’s great content. If you want the fast-forward version, here it is:

- When you work/study, take frequent breaks. Studies shows your concentration lags at about 25 minutes in. If you go over that, every minute after that is going to be diminishing returns.

- But here’s the kicker: it only takes about five minutes to restore “concentration energy.” You can come back to work and start over like you’ve hit re-set.

- Reward yourself on those breaks. Make it as pleasant as possible! View yourself as a dog. Early on, when you train a dog, you have to constantly reinforce the new behavior with lots of treats while their brain makes the association.

- Optimize for energy. Lobdell got great grades in college because he started studying in the afternoon, when he still had energy, and finished at night, when he could reward himself with a beer. He said his friends hadn’t even started studying at that point, telling themselves they’d do it later. When they had lots of energy at … 1 a.m.? Terrible system. Optimize your system for energy.

- If you want to remember something, review it the same day you learn it. Don’t just read and then leave. Read, highlight, and then write your own “chapter summary” before moving on. This is a study tip, but essential for anyone who wants to retain more information. You can do it on this post and take 50% more away from it than you otherwise would have.

- Create a dedicated study area. You know how sleep experts say only to sleep and other things in your bed? Do the same for your work or study if you can. Associate “I’m sitting here” with “work time.” And if you can’t do that, buy yourself a lamp. Light the lamp when it’s work time. You want a clear boundary between work and play. A study found this tip alone made students one full letter grade better.

Note: I also include a section at the bottom of this post so you can learn more about retaining memory, if you ever feel like doing that. But since I assume most of my audience is post-college aged people, feel free to skip it. The above is enough to change how productive you are.

Now, let’s explain it all.

Don’t Buckle Down: It Makes You Hate Work

In college, Marty was dating a freshman named Jeanette. (Follow along with Marty at 2:40). Jeanette struggled in her first quarter: a D average.

Like any naïve young college student, she thought the prescription for this malady was more work.

Harder studying. “Buckling down.”

To fix this, she took what many people assume to be the right approach. She created a system, rather than a goal. Rather than saying, “I’m going to improve by a grade in every class,” she set about creating a system to make the better grade inevitable.

Her system? More work. Harder studying. Buckling down. To the tune of six hours every night, Sunday through Thursday.

Sounds like a good idea, right? Higher grades must be inevitable at that point.

But she ended up failing every class.

What happened? She designed the wrong system. It was the opposite of how our brains work.

The idea of studying harder killed her chances. In fact, it made certain that her study time accomplished two critical things that virtually assured failure.

Jeanette didn’t reward herself for her study sessions

Back to Jeanette in a minute.

First, let’s talk about dogs.

Ever hear of “clicker” training? You’ll see it all over the Kikopup YouTube Channel. The premise is simple: when you see a dog give you the behavior you want, you make a trigger noise (like a clicker) that announces a reward is imminent. Then you reward.

Here’s an example: fixing a dog’s bad habit of leash pulling.

Our instinct is to punish a bad habit. Negative reinforcement for a negative behavior, right?

But Kikopup is more thoughtful than that. She sees that that to the dog, a bad habit like leash-tugging occurs because tugging the leash is more rewarding then the alternative. Her mission? Making avoiding leash tugging more rewarding.

She solves it two ways:

- Taking the dog on a walk, and dropping a treat when it’s in a good position

- Simply stopping when the dog starts tugging, then patting and calling to get the dog back to a loose-leash position.

By the end of the video, you see the dog happy, trotting next to its owner with a loose leash, and paying attention to the owner because of the possibility of reward.

No negative reinforcement required.

It’s just one example of Kikopup’s approach. She has all sorts of creative training solutions that never require negative reinforcement. It seems as though every time she wants a new behavior, there’s a reward-based training method available instead.

What does this have to do with Jeanette?

Jeanette did the opposite.

Jeanette’s system was to sit at her desk for six hours, no matter how she felt. She was engaging that credo that willpower is everything. This is the big mistake: we think our choices are the result of willpower, when just as often they’re the result of our pre-trained reward systems.

By making her life miserable, she was telling her brain:

- Study = bad

- Free time = good

When you start to feel weak and hungry and tired and bored, guess what looks extra tempting? Not studying at all. Then you associate the reward with not studying, and you have yourself a negative feedback loop.

Failure, at that point, is inevitable.

Jeanette made sure every study session was as inefficient as possible

You might think so what if Jeanette is miserable? At least she had the willpower to sit at that desk, right? That’s a lot of work. Day in and day out, six hours a day. Those are nigh-on Olympic athlete levels of commitment. That should result in some improvement, surely.

Yet she failed every class.

If willpower alone is the key, she should have improved her grades, not gotten worse.

So what happened?

According to Marty, she wasn’t really studying all that much.

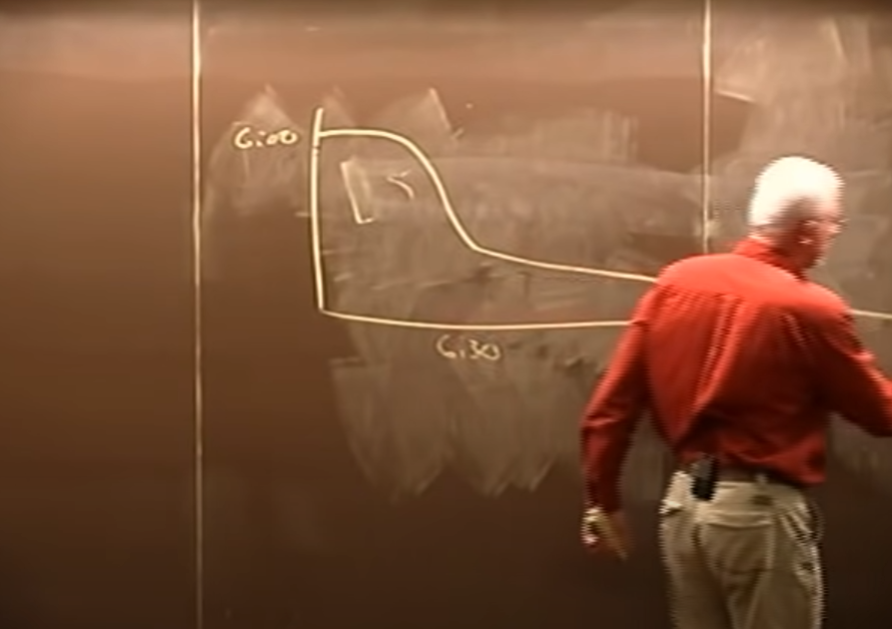

He cites a University of Michigan study that followed students. (Follow along at 1:40 for the study) The researchers wanted students to note how long they’d been studying when they started to feel their eyes glaze over.

It was about 25-30 minutes in.

The “six hours” system guaranteed that Jeanette was remembering as little from each session as possible. She was chasing diminishing returns. Here’s how Marty draws it:

For all those hours chained to her desk, Marty contends, Jeanette was really getting about one 25 minute session in each time.

The rest was misery and exhaustion.

So how does anyone study for long periods of time? Turns out, Marty says, you can “recharge” back to normal levels of energy and attentiveness with about a five minute break. He says to go do something fun for five minutes when you feel your eyes starting to glaze over.

Had she done that rather than the “willpower” method, Jeanette would have gotten about 5.5 hours of good study time for those six-hour sessions. Rather than 25 minutes.

All that pain for about 25 minutes of good, productive work.

This is not ideal.

Plan Your Day Right: Create a Preparation -> Work -> Reward System

“Bitter are the roots of study, but how sweet their fruit.”

Cato

Remember we said we’d circle back to the idea of rewards? Here’s how Marty did it himself:

Marty would study in the afternoon. His goal was to get the studying out of the way so he could go to a local tavern and have a few beers as his reward.

His buddies were absolutely mystified by this. They wondered how he was getting straight-As if they saw him at the bar drinking beer every night.

He did it because he followed the right pattern:

Preparation for Work -> Work -> Reward.

Meanwhile, those buddies he saw out at the bar? They hadn’t even started their studies yet. They were giving themselves rewards for doing nothing. And by rewarding that behavior, they were training themselves to do exactly that. Nothing.

Sure, they might have told themselves they were going to study that night. But how realistic is it to study when you’ve been giving yourself nothing but rewards for avoiding that studying?

Take me. As I sat down to start working on this post, I was doing some online shopping. As I write this, I have some bonus cash in my credit card account I get to spend, guilt-free.

Of course, searching for free rewards before writing this post is a terrible idea. It’s telling my brain: “yes, yes, do THIS. No, don’t do that painful blog-writing thing, there aren’t any rewards with that.”

If you want to actually create a long-term habit, you have to get the order right. And it has very little to do with willpower.

It has more to do with the reward-seeking systems in your brain, and how you use them. Simply put:

Things that are reinforced, we tend to do more of. Things that are punished or ignored, we tend to do less of.

I’ll buckle down and work hard is the worst approach to creating consistent achievement. It virtually ensures that you’ll waste as much time as possible while transforming your work into a joyless existence.

Tweet

So what do you do instead? Marty has a few recommendations.

- [Preparation] Create a dedicated study area. You need a place you can go that your brain associates with only studying. If you don’t have a place, use a public library. One study found that something as simple as using a “study lamp” used only for studying could increase success by one full grade on average. Here’s Marty talking about the study. You want your brain to think “when this lamp is on, I’m working.” Turn it off in the next step. Click here for the timestamp where Marty talks about the benefits of a dedicated study zone.

- [Work] Take 5 minute breaks every 30 minutes. We know two things thus far: we have about 25-30 minutes of attention to give at once, and it only takes about 5 minutes of rest to regenerate the energy we need. Using the Pomodoro Technique, you’ll find the work far more sustainable.

- [Reward] Reward yourself in those five minutes. Leave your study zone for your reward. Then, do whatever you like. Eat a snack. Listen to some music. Enjoy yourself as fully as possible for five minutes to reinforce the behavior. Train yourself like a dog. You want your brain to think “study/work session = awesome treat time.”

With this preparation -> work -> reward system, you’re training yourself to give dedicated, engaged bursts of work in a way that doesn’t drain your energy. Just like a dog thinks “leash = outside,” you’re going to think “study lamp -> study time.”

My fellow freelancers can apply this to freelance work. “Freelance lamp -> freelancing time.”

The more automatic it becomes, the less you’ll come to rely on willpower.

The More Active You Are in Studying, The More Effective You’ll Be

Stick to the tips above and you’ll have enough to make yourself work more frequently without using willpower.

But what if you’re a student reading this, or an adult who’s doing something like learning a language or taking an online class?

You’ll still want to know how to retain as much information as possible.

The simplest way I can think to sum up Marty’s opinion on retention is this:

The more active your learning is, the more you’ll remember.

Tweet

If all you do during a “study session” is read, you’re going to retain something, sure, but nothing compared to what you could do.

And after all, 25 minutes of hard studying is time away from your family. Time away from your favorite recreational activities. Time away from everything, anything else.

Doesn’t it make sense to optimize that time?

You’re with me so far. But what does “active” mean, and how do you turn it into actionable work? Here are some tips to kick you off:

- Don’t just read and highlight. Review your notes and take notes on those. Most people assume that sitting down, reading, and highlighting a book is “studying.” Not so. Why not? If you’re only taking notes for later, you’ve only done half the work of a study session. You’ll forget it all by next time. Marty recommends immediately reviewing the notes you took in the same session, and then expounding upon them. Write a little bit more about them. Digest them. What do they mean? Your brain will assign significance to repeatedly-viewed concepts, and remember them.

- Being reminded is not “remembering.” Why isn’t it enough to highlight or take notes once? Because when you review those later and you “remember them,” you’re misleading yourself. You’re really just being reminded of them. But you don’t remember something until you can pull up the concepts yourself, without reminders.

- Here’s how to tell if you remembered a concept from your notes. After reviewing your notes and expounding on an idea, move on to the next one. Review that one. Now, go back to the original idea, but don’t think of your notes. Can you look at the sky and still remember what you were reviewing? If so, you remember it.

- Pull on existing concepts to remember something. Colors of the rainbow? ROY G BIV. This works because you take your name recognition brain-software and apply it to remembering colors. How well can you remember YTRHAUSPDPAYH? Not so well. Find out that it’s just a scrambled version of HAPPY THURSDAY, however, and you’ll remember it every time.

- Get more REM sleep. For whatever reason, REM sleep is vital for memory consolidation, so make sure you’re getting it. A whole other post in and of itself, but worth looking into books like “Why We Sleep” by Matthew Walker for more information. As Marty points out, it’s a common problem for people with sleep apnea: they often struggle to remember things.

- To learn something new, determine to find it. If you look at a puzzle trying to find blue pieces, your brain is going to alert you when you find blue pieces. The same applies to new concepts. Many of us go into a new book planning to let the author telling us everything we need to know. But if you have an idea of exactly what you want to learn (say, going into “Why We Sleep” wanting to get better at REM sleep), then you’ll have a filter that will help you identify specific tips. And you’ll find it easier to remember those tips.

Maximizing Work (Conclusion)

I didn’t write this post because I’m a productivity guru who figured out how to work 16 hours a day. I did it because I’m the opposite. I can’t stand work for work’s sake.

And that’s exactly what poor study habits are. Work for work’s sake. Why study for six hours a day just to fail at the end of the semester? You can have the same results for 0 hours a day.

It’s the same with your own approach to productivity. If you can…

- …create an environment where work is easy to begin and inevitable

- …learn to work for larger chunks of uninterrupted time

- …shut off that work at the end and reward yourself

- …prioritize managing your energy rather than your time

… then your productivity—and overall work satisfaction—will go up.

To leave you off, here’s how the current workday is looking as I finish this.

That’s several hours of “very productive work,” as measured by RescueTime. Yet notice the polarity of the hours. One hour is very red, the next very blue. (Those hours with half red? Yep, that was one split hour when I was doing whatever I wanted.) I’m not constantly distracted, constantly shifting between tasks.

One task at a time, baby. One at a time.

And what are the results of this system? As I write this, I beat my financial earnings goal for the day. I worked hard and finished my assignments. Here I am at 4:10 p.m., at the end of a 3,000 word blog post, still energized, with 50 minutes left until five o’clock. The time I use for the rest of the day is mine completely, with no unfinished tasks lingering over me.

What to do with that time?

Maybe I’ll go to the pub.

Studying stinks. Instead of studying how to write posts like these, why not just hire someone like me to write them for your blog, business, or website?